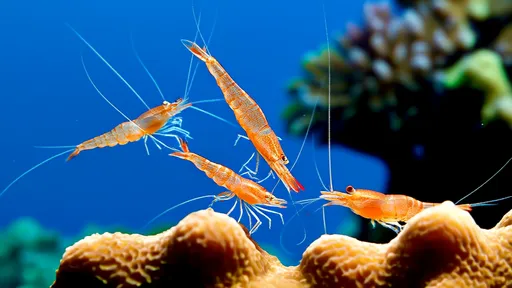

The Crimson Shrimp: Masters of Deep-Sea Pressure Adaptation

In the crushing darkness of the deep ocean, where pressures reach unimaginable levels and temperatures hover near freezing, life persists in ways that continue to astonish scientists. Among these remarkable survivors is the crimson shrimp, a creature that has evolved extraordinary adaptations to thrive where most organisms would perish instantly. These deep-sea dwellers, often found at depths exceeding 3,000 meters, represent one of nature's most fascinating examples of extreme environment adaptation.

The deep sea presents challenges that would be fatal to surface-dwelling creatures. At these depths, pressures can exceed 300 times that of Earth's atmosphere, enough to crush submarines and most man-made equipment. Yet the crimson shrimp moves effortlessly through these conditions, its body perfectly engineered by evolution to withstand forces that seem impossible to survive. Their secret lies in a combination of physiological and biochemical adaptations that have taken millions of years to perfect.

Physiological Marvels

Unlike their shallow-water relatives, crimson shrimp possess bodies that are fundamentally different in structure. Their exoskeletons contain unique protein structures that maintain flexibility under extreme pressure while preventing collapse. These crustaceans have evolved a special cartilage-like material in their joints that remains pliable even in the deep ocean's intense environment, allowing for normal movement where rigid structures would fail.

Internally, their organs are protected by a gel-like substance that maintains equal pressure with the surrounding water, preventing the catastrophic implosion that would occur in most other creatures. This adaptation is particularly crucial for their swim bladders, which in deep-sea species have become solid structures rather than gas-filled chambers. The transformation of this organ demonstrates nature's incredible ability to re-engineer existing biological systems for new environments.

Biochemical Innovations

At the molecular level, crimson shrimp exhibit equally remarkable adaptations. Their cellular membranes contain unusually high concentrations of specialized lipids that maintain fluidity under extreme pressure. Normal cell membranes would become rigid and nonfunctional at such depths, but these deep-sea creatures have evolved membranes that remain flexible and functional regardless of environmental pressure.

Their proteins, particularly enzymes, have unique three-dimensional structures stabilized by additional molecular bonds. These pressure-resistant enzymes allow metabolic processes to continue normally where conventional proteins would denature. Perhaps most astonishing is their hemoglobin, which binds oxygen with extraordinary efficiency in the cold, oxygen-poor depths. This adaptation allows them to extract every possible oxygen molecule from their environment, a crucial ability in their resource-scarce habitat.

Behavioral Adaptations

Beyond their physical and chemical adaptations, crimson shrimp have developed behaviors that maximize their survival in the deep sea. They move with slow, deliberate motions to conserve energy in an environment where food is scarce. Their hunting strategies take advantage of the pressure conditions, using minimal movement to ambush prey that may be similarly constrained by the extreme environment.

Reproductive behaviors have also adapted to the challenges of deep-sea life. Crimson shrimp produce relatively few offspring compared to shallow-water species, but invest more energy in each one. Their larvae develop protective features early, allowing them to survive the same pressures as adults from a young age. This represents a different evolutionary strategy than their surface-dwelling cousins, prioritizing quality over quantity in reproduction.

Scientific Significance

The study of crimson shrimp offers valuable insights for multiple scientific disciplines. Marine biologists gain understanding of how life can adapt to extreme conditions, potentially informing the search for extraterrestrial life in similarly hostile environments. Their pressure-resistant enzymes have attracted interest from industrial applications where processes occur under high pressure. Medical researchers study their unique biochemistry for potential applications in treating pressure-related injuries in humans.

Perhaps most importantly, these creatures serve as indicators of deep-sea ecosystem health. As human activities increasingly impact even these remote depths, understanding creatures like the crimson shrimp becomes crucial for conservation efforts. Their specialized adaptations make them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes, serving as early warning systems for disturbances in deep-sea ecosystems.

Future Research Directions

Despite significant advances in understanding these remarkable creatures, many mysteries remain. Scientists are particularly interested in how crimson shrimp larvae survive the transition from surface waters, where many species begin life, to the crushing depths of their adult habitat. The genetic mechanisms behind their pressure adaptations represent another area of active research, with potential applications in biotechnology.

New deep-sea exploration technologies are allowing researchers to study these shrimp in their natural habitat with minimal disturbance. Advanced imaging systems can now capture their behaviors without the need for capture or pressure changes that might alter their natural physiology. These technological advances promise to reveal even more about how life not only survives but thrives in one of Earth's most extreme environments.

The crimson shrimp stands as a testament to life's incredible adaptability. In the silent darkness of the deep ocean, where humans can only visit briefly with sophisticated equipment, these creatures go about their lives with effortless grace. Their existence challenges our understanding of life's limits and continues to inspire scientific inquiry into how organisms can conquer even the most hostile environments on Earth.

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025