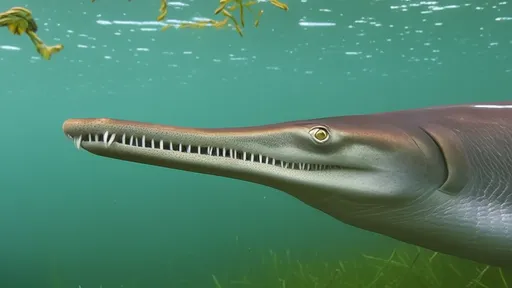

The ocean's depths hold countless mysteries, but few are as mesmerizing as the thresher shark's hunting technique. With its extraordinarily elongated tail fin—sometimes as long as its body—this predator has evolved a unique propulsion system that defies conventional aquatic locomotion. Recent studies reveal how the thresher shark's tail functions not just as a rudder, but as a biological accelerator capable of generating bursts of speed exceeding 30 mph in milliseconds.

Unlike most sharks that rely on body undulation for movement, the thresher employs its caudal fin like a whip. High-speed footage shows the tail moving in a perfect arc, creating a pressure wave that stuns prey. Marine biologists at the Scripps Institution discovered that the tip of the tail actually breaks the water's surface during strikes, producing cavitation bubbles that collapse with enough force to kill small fish. This phenomenon, typically observed in military torpedoes, makes the thresher one of nature's most efficient underwater hunters.

The anatomy behind this evolutionary marvel is equally extraordinary. MRI scans of preserved specimens show hypertrophied muscles at the tail base containing super-fast glycolytic fibers similar to those found in sprinting cheetahs. These muscles comprise nearly 30% of the shark's total mass—an unprecedented adaptation among elasmobranchs. The vertebral column also exhibits specialized flexibility, with interlocking bony processes that prevent dislocation during extreme tail movements.

Researchers from the University of Hawaii recently demonstrated how threshers optimize their tail strikes through computational fluid dynamics. Their models indicate the tail's unique curvature—measuring precisely 17 degrees at maximum flexion—creates a vortex ring that concentrates kinetic energy. This explains how a 500-pound shark can accelerate its tail tip to nearly 80 mph during a hunting strike, generating enough force to knock out multiple sardines simultaneously.

Climate change may be altering this perfected hunting strategy. Rising ocean temperatures appear to affect the thresher's tail musculature efficiency, with thermal imaging showing decreased performance in waters above 24°C. Conservationists warn that warming seas could force these sharks into deeper, cooler waters where their surface-hunting techniques become less effective. Tagging studies off the Philippines reveal threshers now diving 30% deeper compared to a decade ago, potentially disrupting their ecological role as apex predators.

The thresher's tail has inspired biomimetic innovations in marine robotics. Engineers at MIT have developed a prototype underwater drone mimicking the shark's tail mechanics, achieving 40% greater acceleration than conventional propeller designs. Meanwhile, naval architects are experimenting with scaled-down versions of the thresher's tail configuration for next-generation submarine maneuvering systems. These applications highlight how evolutionary adaptations perfected over millions of years may revolutionize human technology.

Despite their extraordinary abilities, thresher sharks face severe threats from commercial fishing. Their magnificent tails often become entangled in gillnets, and the species' slow reproductive rate makes populations particularly vulnerable. Marine protected areas established in the Coral Triangle have shown promising results, with thresher numbers rebounding by 18% in monitored zones. However, with an estimated 90% population decline globally since the 1980s, the future of these aquatic acrobats remains uncertain.

New satellite tracking data reveals another surprise—threshers undertake transoceanic migrations previously thought impossible for the species. One female tagged near Bali was recorded swimming over 8,000 miles to the Seychelles, demonstrating endurance that contradicts earlier assumptions about their energy expenditure. This discovery has prompted calls for international conservation agreements to protect migration corridors that may be critical for the species' survival.

The thresher shark's tail represents one of evolution's most spectacular examples of specialized adaptation. From its biomechanical perfection to its growing list of human applications, this natural marvel continues to captivate scientists and ocean enthusiasts alike. As research progresses, each new finding underscores how much we still have to learn from these extraordinary creatures of the deep.

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025